On November 21, 2017, The Genron NPO hosted an afternoon forum in Tokyo titled, "How can we address the challenges to liberal democracy?"

Hosted and moderated by Genron President Yasushi Kudo, the presentations and discussion provided the audience with a better understanding of the background of the issues faced, and of future efforts aimed at dealing with the crisis, from the perspective of five distinguished guests from various backgrounds.

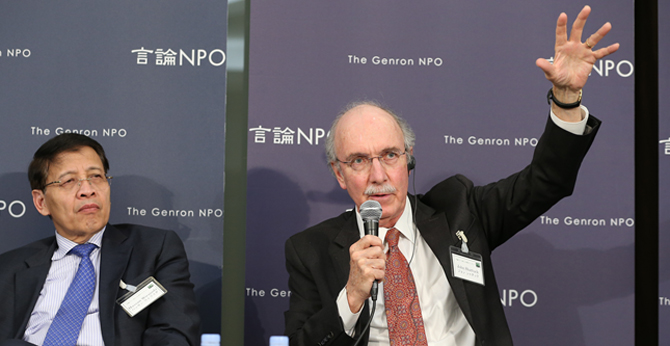

First to present was John Shattuck, Senior Fellow at the Carr Center for Human Rights Policy, Harvard Kennedy School. Shattuck has also served as President and Rector of Central European University, and is a former United States Assistant Secretary of State for Democracy, Human Rights and Labor.

Shattuck described "liberal democracy" as a pluralist, complex system, with a variety of institutions that include voting, free media, independence of the judiciary, and more. This form of democracy has made some significant achievements over the last 50 years, providing peace and stability, and a high degree of freedom and prosperity, in many countries.

However, Shattuck warned, liberal democracy "is under attack internally, particularly in the west, in a way that it hasn't been for a very long time." Democracy has served as a "bulwark against authoritarianism," he explained, but there are authoritarian elements rising against it.

He pointed to three signs of the "outright rebellion" visible in western populism.

The first is economic, and is rooted in the people who feel left behind by lost industries, the forces of globalization, and introduction of new technologies. This has led to a political shift of blue collar workers from moderate left to the extreme right, many of whom helped elect Donald Trump.

The second is the "cultural rebellion" led by those previously dominant groups who feel left behind as society becomes more multicultural and egalitarian. Finally, the third - possibly connected to the second - is the "security rebellion" which has seen increased hostility to migrants, immigrants, and others.

Populism, Shattuck argues, is the antithesis of democracy as it opposes liberal democracy's central framework, which includes pluralism, compromise, and minority rights.

"How resilient is democracy?" Shattuck asked. He is optimistic, and believes that recovery is possible, though it will take a lot of work. He reminded the audience of the words of Winston Churchill, who once said that "...democracy is the worst form of Government, except for all those other forms."

Hassan Wirajuda, former Minister of Foreign Affairs (Indonesia), provided a brief overview of the current state of liberal democracy in Asia as a whole, and in Indonesia in particular.

"For the whole world to address the challenges to liberal democracy," Wirajuda said. "We should have the ideal states of democracy at the global, regional, and national levels."

Wirajuda believes there is a lack of democracy at the national level, where political and economic security is "very much divided in to class, with the most powerful and privileged (at the top), followed by the rest."

He did note that efforts to reform such institutions have been proposed, but all of them have thus far failed. The issue is greater than just the weakening of global order, however. It has been further weakened by the recent U.S. withdrawal from its former role as world leader, which Wirajuda says has "put the world in disarray".

Regarding Asia, Wirajuda believes that it is far behind Latin America and the European and Africa Unions in terms of democracy adoption. Only one third of Asian countries are "free democracies," with another third running elections "without integrity", and the rest being purely authoritarian. For this reason, Wirajuda believes it is difficult for Asia to even begin talking about the idea of liberal democracy being "in decline," as democracy has yet to take hold in the region.

He pointed to India and Indonesia as successes however. These two countries have shown that the democratic decision process "is noisy and messy", but they have also risen to become two of the three fastest growing economics in the world. Indonesia is the third largest democracy following India and the U.S., but enjoys a voter participation rate of 70 to 80%, which is higher than the U.S. It is also the largest Muslim country in the world, so they are "proving that Islam, democracy and modernity" can go hand in hand. In these ways, Indonesia is a model for success, Wirajuda believes, but he warns that democracy is "a work in progress and we should not take our gains for granted...we need continuous reform."

Myron Belkind is a lecturer at George Washington University and former President of the National Press Club. Kudo asked Belkind to discuss the role journalists play in a democracy, and he began his presentation by presenting a few vignettes from his career that illustrate the impact journalism can have.

He spoke of Indira Gandhi's imposition of the state of emergency in India between 1975 and 1977. Although India had been the world's largest democracy up until that point, Gandhi's declaration resulted in a brief period during which her opponents were imprisoned and the media was strictly censored. To Belkind, this illustrates Gandhi's recognition of the power the press can wield.

He also spoke of an interview he conducted with Zulfiqar Ali Bhutto, former president and prime minister of Pakistan, who complained about his opponent's control of the media, then went on to manipulate and control it in the same way when he rose to power.

Finally, he related an anecdote regarding his last day working for the Associated Press, when he was invited to the Imperial Palace in Tokyo for a reception. He and his wife joined the receiving line to greet the Emperor and Empress, and when Belkind mentioned that he was retiring, the Empress responded by saying, "Journalists are very important because they inform society, and international journalists are important because you inform the rest of the world about Japan."

Belkind believes that today the media and democracy are facing major challenges in Washington, some unprecedented, and though democracies take various forms, he asserted that the most important question in a democracy is "whether it has a truly active and free press."

"Many presidents have been critical of the press," he told the participants. "But for the first time, we are having an open assault on the First Amendment."

He assured the audience that not everything is pessimistic, and pointed to the Washington Post, which now has the statement "Democracy dies in darkness" on its front page, as an example of the media continuing to do its job. The Post "recognizes that it is the media that has to shed light on democracy."

Overall, Belkind said that there are four things must happen to protect and foster democracy in the U.S. First, the U.S. must have greater voter participation. Second, there must be a removal of voting restrictions imposed to make registration of certain voter demographics difficult. As a part of this, gerrymandering and redistricting must also be restricted. Third, the judiciary must remain independent. Finally, the people must support the media by subscribing.

"It is but a small investment to protect the most important element of liberal democracy," he said. "If these challenges are met, democracy will thrive and not die in darkness."

Jonathan Soble is a Tokyo correspondent for the New York Times, and he provided another journalistic perspective, pointing out that the threat to the media is actually a subset of the broader threat to institutions caused by the rise in populism. The term populism is difficult to define, Soble admitted, but he said that it could be defined as "a dislike of institutions, a dislike of legislatures and courts and civil services and political parties...and a part of that set is media."

The claim on the part of populists is that those institutions are "rotten" and aren't serving the people. So, with populism, "what you are left with is the will of the people and a leader who interprets that will."

Trump's rise to the Presidency has been described as a success of populism, and Soble suggested that there is a darker motive behind Trump using Twitter to communicate with his base. Perhaps his aim is to "push away any institution that gets in the way of his interpreting the people's will."

Previous panelists asserted that the ideas of debate and consensus are essential parts of a liberal democracy, and while Soble agrees with their importance, he pointed out that they are not the entire purpose.

"Democracy exists to make decisions in the absence of consensus. In a healthy democracy, we talk to each other, look for compromise, etc., but we are not going to agree perfectly...and that's when the mechanism that makes democracy unique comes into play."

In essence, the people vote, and ideally they vote with the belief that their vote counts as much as the vote of any other person. This assures them that although they won't achieve their goals every time, they will always get another chance to express their desires through voting. Soble sees this ideal as having fallen slightly by the wayside in recent years, however, as, "The problem now is that people see the other side as illegitimate. That's when things start to unravel."

Kudo turned to Akiko Yamanaka, the current Vice Minister for Foreign Affairs of Japan, for her opinion on the low levels of trust the Japanese people have in political parties and the Diet.

Yamanaka referred back to Shattuck's point regarding resilience, and pointed out that the Japanese Diet has never had a full discussion or debate about the future of Japan. Other democratic countries include such debate in parliamentary proceedings, with one example being Question Time in the United Kingdom, during which the Prime Minister responds to questions from parliament every Wednesday for 30 minutes. Perhaps, she suggested, such discussion can be beneficial.

Yamanaka hesitates to compare too much to other countries, as she is skeptical about what truly defines a democracy. One thing she seems certain of is that the government must consider more than just productivity and efficiency - it must also consider the overall happiness of the populace.

Every country has its own issues, Yamanaka explained, and whether those issues or solutions are democratic in nature or not is a question that each country must answer alone. "But we have to come back to the question of balance," she said. "Democracies have to ask themselves what kind of country they want to be, and think about the essence of that government."

Kudo returned to Soble and asked if he had any insight to offer regarding the state of Japanese democracy from his perspective as a long-term resident of Japan.

Soble explained that, in some ways, he sees Japanese democracy as "an enduring mystery."

"On one hand, the same party (the Liberal Democratic Party (LDP)) has governed for the last 60 years...but opinion polls show that the LDP doesn't actually have much support."

He also pointed to what he described as the "slightly unusual...symbiotic relationship between opposition and ruling parties" as another interesting element of Japanese politics. There is consensus regarding debate, and much discussion, but Soble said that all that discussion seems to be "predicated on the assumption that the opposition will never win."

The focus is on the process, but "in a different way that is uniquely Japanese." Soble wondered if these characteristics are what have enabled the one party to remain dominant.

In the final part of the discussion, Kudo asked the participants their opinions on how to approach the challenges facing liberal democracy. Hassan Wirajuda responded that sometimes the rights of the people must be limited "for sake of national security, public order, public health and other such issues." These sorts of limitations are acceptable, he said, if they are described by the rule of law.

Shattuck disagreed with Wirajuda's statement, however, pointing out that one danger in proscribing precise limits on people's rights, even when codified in law, is that "different cases are going to seem related and you don't want them to be."

Sobel pointed out that while President Trump came to power on a "wave of anger," but some of the issues raised are valid, and "we have to recognize that and think about what can be done."

He also considered Kudo's question from the journalist's perspective, concluding that, "We are fighting a losing battle against technology and a president that dislikes us, so we have to keep our house clean."

Yamanaka believes that education is the way forward, beginning in schools with education about the essential tenets of democracy.

"Students need to learn that when a majority decision is made, we need to follow it," she said. "But when a decision is poor, you get to choose another government later."

That point is also important on an international level, Yamanaka said. Being able to select the path a country takes when implementing democracy is necessary, but so is having the option to adjust that path part way through to tailor it to each country's needs.

For Yamanaka, balance lies at the heart of the issue, from the global-regional balance, to the balance between technology and privacy. Japan's privacy protections are good, she explained, but work-life balance is not at the level it needs to be. That includes the balance between genders, career-family balance for women, the balance between managerial and non-managerial positions, and the balance between national and international interests.

Yamanaka agrees that people need to think about the purpose and goals of democracy, but she also believes that we must think about what kind of education is needed to ensure that have a brighter future.

Post a comment